On the 30th of March 2007, the Gunditjmara people were granted Native Title for approximately 140,000 hectares of land, rivers, reserves, national parks, creeks and sea.

When the First Fleet arrived on our shores and claimed the land as ‘crown land’ they also falsely claimed it to be ‘terra nulius’ meaning that it belonged to no one and disregarding the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples clearly living on the land. The 1992, verdict of Mabo v. Queensland no.2 was delivered, it stated that the Meriam people had ‘Native title’ to their land and effectively abolished terra nullius.

Following this, the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) was passed to help with the uncertainty regarding land rights and native title. The Native Title Act aimed to achieve four main objectives:

- To provide for the recognition and protection of native title.

- To establish ways in which future dealings affecting native title may proceed and

- to set standards for those dealings.

- To establish a mechanism for determining claims to native title.

- To provide for, or permit, the validation of past acts, and intermediate period acts, invalidated because of the existence of native title.

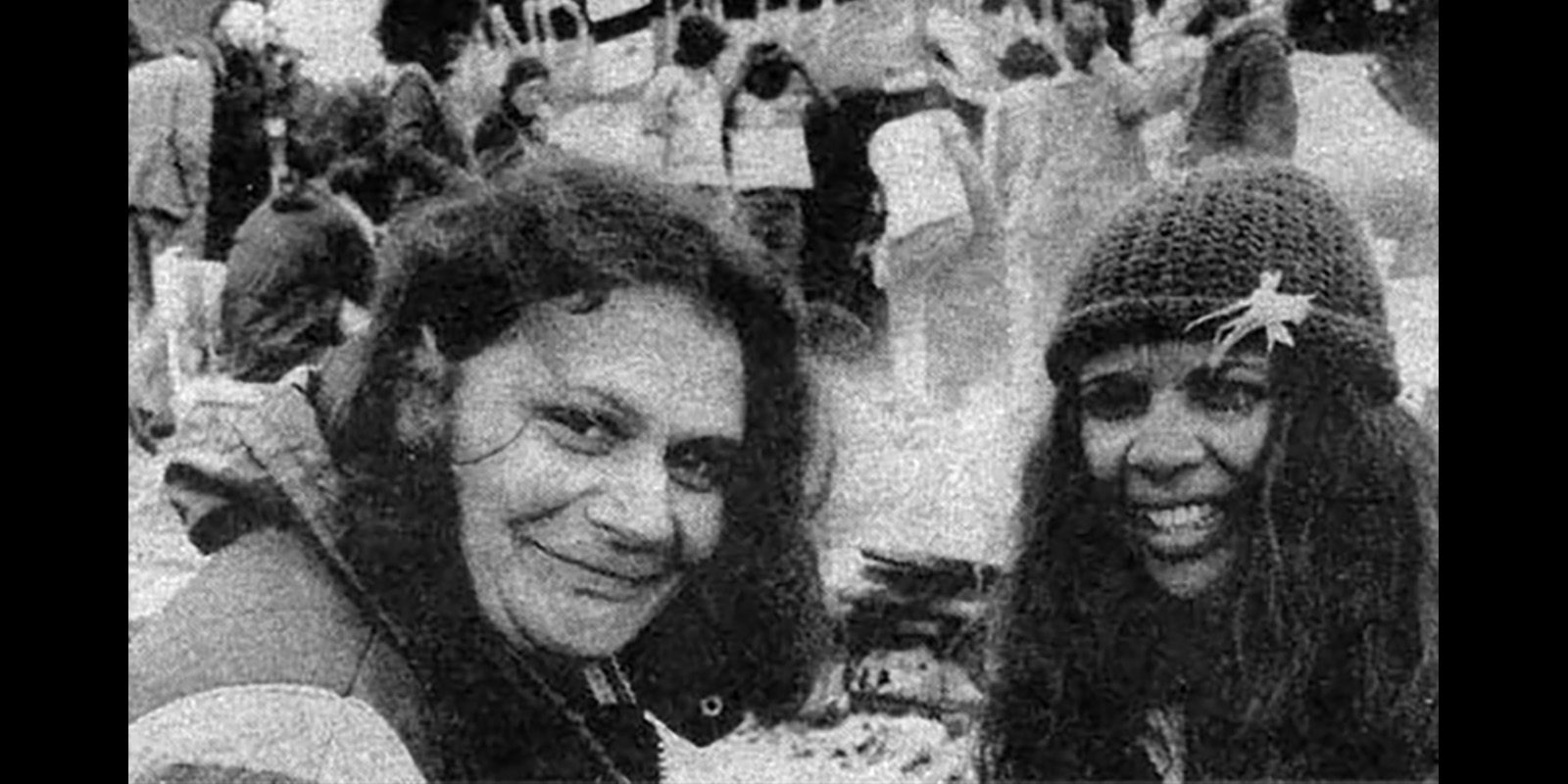

Aunty Sandra Onus and Aunty Christina Frankland, leaders in the struggle, at the protest camp in 1980. The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story.

Onus vs Alcoa

In the early 1980s, a decade before the Mabo v Queensland decision regarding Native title, Gunditjmara gained national attention after they successfully fought for recognition of their rights as traditional custodians of their land.

This legal battle began over an aluminium smelter that was proposed to be built near Portland. Sandra Onus and Christina Frankland went up against Alcoa of Australia Ltd in the Victorian Supreme Court to prevent them from damaging or interfering with any of the cultural sites located on the proposed site for the smelter.

The supreme court required that Onus and Frankland prove they had a ‘special interest’ in protecting their cultural heritage under the Archaeological and Aboriginal Relics Preservation Act 1972 (Vic). Their case was dismissed in the Supreme Court however they then took it to the High Court where they were successful.

The case set a precedent regarding protection of Indigenous peoples land and heritage. The premier of Victoria offered to implement a range of policies that would see 53 hectares of land including the Lake Condah Mission handed back to the Gunditjmara people in return for the legal action against Alcoa to be dropped. The handover ceremony took place at Lake Condah in 1988.

“...recognition of traditional ownership, connection to country, the importance of cultural heritage ... everyone was just so happy” - Aunty Denise Lovett

Lake Condah. Author - Tyson Lovett-Murray © Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners. Source: UNESCO.

Gunditjmara Native Title

The Gunditjmara people launched their native title claim in 1996 however it took 11 years to reach an agreement with the Victorian government. In 2000 the state government committed to approaching native title through mediation (allows parties to have discussion) rather than litigation (legal action) and in 2002 Gunditjmara and the State government entered into mediation.

This however stalled and Federal Court judge Justice North had to intervene. He used the Court’s power to move the case back to litigation and ordered an early evidence hearing in March and April 2005. This pressured the State to come to a fair and timely settlement, and pressured Gunditjmara to keep up with the new timetable. A ‘conference of experts’ was held in which experts of both parties were told to identify any areas of dispute about the mobs connection to Country. Connection reports were also written up by anthropologists, linguists, and historians. These reports went to both parties as well.

The native title consent determination was agreed to on the 30th March 2007 and covered roughly 140,000 hectares of vacant ‘Crown’ land rivers, reserves, national parks, creeks and sea.

The native title rights are non-exclusive meaning they exist on shared land. The rights include:

- the right to have access to or enter and remain on the land and waters.

- the right to take the resources of the land and water.

- the right to protect places and areas of importance on the land and waters.

“[Native title] puts local tribes and councils on notice that they now have to deal with us as a people when they want to do whatever they used to just think they had the right to do.” – Uncle Johnny Lovett

You can read more about Onus v. Alcoa, native title and more in The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story.