Māori people are the Tāngata Whenua (people of the land/Indigenous People) of Aotearoa (Land of the Long White Cloud, known colonially as New Zealand).

Māori people belong to Iwi (tribes) and Hapu (extended family groups). There are over 100 Iwi in Aotearoa. All Māori people have a connection to their ancestral mountain, river and sea or lake and trace their whakapapa (ancestry/genealogy) to a Waka (ocean-going canoe) that brought their ancestors to Aotearoa from Hawaiki, the home of all Polynesians.

There are around 745,000 Māori living in Aotearoa, comprising around 15% of the total population and 1 in 6 Māori live in Australia.

Creation

Māori have many stories relating to the creation of the Earth, people and Gods. An important story is that of Ranginui the Sky Father and Papatūānuku the Earth Mother. Rangi and Papa lay together in a tight embrace. They held each other so tightly that no light could get through and the world was in darkness.

Rangi and Papa had many children who lived between them. The children wondered what light was like and were fed up with living in darkness, cramped between their parents. Tāne Mahuta, the God of the forest, decided that they should split their parents apart so the Sky would be above them and the Earth beneath their feet.

After all his brothers were unable to separate their parents, Tāne Mahuta put his head to the ground and used his feet to kick away his father Rangi. With Rangi and Papa separated, in came the world of light (Te Ao Marama) and humans flourished on the Earth. However, Rangi still mourns the loss of Papa and drops tears which become dew and Papa’s sighs go up to the sky, which become mist.

This song and cartoon depicts the Māori creation story about Ranginui the Sky Father and Papatūānuku the Earth Mother.

Image source: Te Ara Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

Culture

Kapa Haka

Kapa Haka is the broad term for Māori performing arts including song, dance, poi (ball attached to rope or string) and haka. Many people are only aware of haka but Māori cultural performance, movement and music contains many different features.

Haka is a famous Māori cultural practice, however many people only view it as a ‘war dance.’ However, haka are also performed as a sign of respect, to show unity and pride and to tell stories of significance for Iwi.

Image source: Rotorua Now, 2019

Whakairo (carving)

The Māori art of carving into wood, stone or bone is known as whakairo. Whakairo requires great skill and patience to carve highly detailed and intricate designs into wood panels for meeting houses, the front of waka or canoes, weapons, jewellery and many other objects. Often, carvings represent important stories, ancestors and symbols.

Image source: Marae in Waitangi, Philip Morton, 100% Pure New Zealand

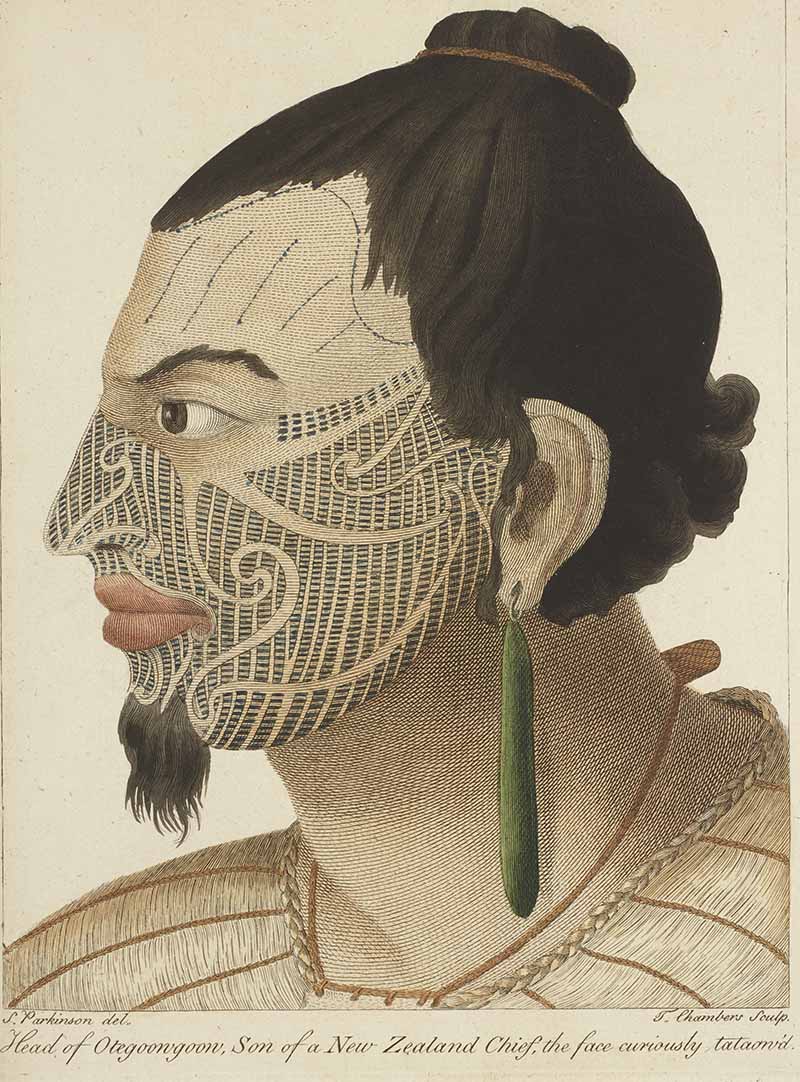

Tā Moko (facial tattoos)

Tā Moko are facial tattoos that represent a person’s ancestry, status, role in society and identity, covering the whole face for men and covering the lips and chin for women. The practice was suppressed by colonisers, however in recent years, many Māori have been reviving Tā Moko.

Image Source: Te Papa

Colonial history and current struggles

Pākehā (Europeans) first visited Aotearoa in 1642 (Abel Tasman) and in the 1770s (Captain James Cook). Whalers, missionaries and traders followed soon after.

In 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed between 540 Māori Rangatira (chiefs or leaders) and the British Crown. The Treaty of Waitangi is seen as the foundational document for the nation of New Zealand and it continues to be celebrated each year with a public holiday.

The Treaty was first signed in the town of Waitangi and was then sent on to be signed by Rangatira in different areas, although not all Iwi (tribes) signed the Treaty. One issue with the Treaty was that the meaning of the text was different in the English version and the Te Reo Māori (Māori language) versions. In the English version, the text stated that Māori were agreeing to hand over their sovereignty to the British. However, in the Māori language version, the term ‘sovereignty’ was translated to kawanatanga (meaning governance). This means that to the Rangatira signing the treaty, they were allowing the British to set up a government but that they would retain their sovereignty and their rights to manage their own affairs.

Conflict between Māori and Pakeha occurred throughout the 1800s, as Pākehā stole more and more Māori land in breach of the Treaty of Waitangi. This period is known as the New Zealand Land Wars. While Māori fought very strongly and had many victories in battle, they were significantly outnumbered by Pākehā. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, more Māori land was taken, cultural practices and language were suppressed and Māori were impoverished as a direct result of colonisation. From the 1920s, more and more Māori moved off their homelands to find work in cities.

In 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed between 540 Māori Rangatira (chiefs or leaders) and the British Crown. The Treaty is seen as the foundational document for the nation of New Zealand and it continues to be celebrated each year with a public holiday.

Image source: New Zealand Government

Keeping culture

Despite the enormous suffering caused by colonisation, Māori continued to stand up for their rights and continue and revive their culture and language. During the 1970s, a significant protest movement developed. Māori fought to get land back and revive their culture. A key example is Māori language. Previously close to being lost, Māori fought hard to revive language by developing courses and all Māori language pre-schools. Although the number of fluent speakers is still low, many Māori are starting their language learning journey. Marae or meeting houses for Māori communities were and continue to be important centres for cultural strength and revival.

Leaders

Below are three important people who have made important contributions to Māori culture and politics.

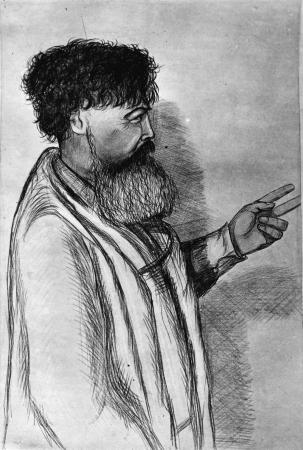

Te Whiti O Rongomai (1830 – 1907)

Te Whiti O Rongomai was a spiritual and political leader who along with Tohu Kākahi founded the Parihaka settlement in Taranaki on the West Coast of the North Island. Following decades of land confiscations of his Te Āti Awa Iwi and other Taranaki Iwi, Te Whiti and Tohu led a movement of non-violent resistance to land theft and colonisation. Their tactics included ploughing land that had been taken by settlers and removing fences. On 5 November 1881, an armed force of over 1600 invaded Parihaka. Rather than respond violently, the Māori at Parihaka greeted the troops with song and bread. Te Whiti is remembered as a pioneer of non-violent resistance to colonisation.

Image source: Te Ara Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

Dame Whina Cooper (1895 – 1994)

A respected Te Rārawa Kuia (Elder), Dame Whina Cooper was a national leader on a range of issues for Māori. She was the foundation president of the Māori Women’s Welfare League and led the 1975 Land March from the top of the North Island to Parliament in Wellington.

Image source: Te Ara Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

Taika Waititi (1975 - )

An internationally known comedian, actor and director, Taika Waititi comes from the Te-Whānau-ā-Apanui Iwi on the East Coast of the North Island. Waititi has brought the experiences of Māori to the screen, notably in his films Boy and Hunt for the Wilderpeople, as well as directing Thor: Ragnarok. Known for the humour he brings to his films, he has been outspoken against racism and he was New Zealander of the Year in 2017.

Image source: ABC News

Additional resources

- Te Papa Tongarewa – Museum of New Zealand

- Te Papa Teaching Resources

- Māori Television

- Huia Publisher

Sources used in writing this article:

- National Library of New Zealand, The Story of Rangi and Papa

- Victoria University of Wellington, Rangi and Papa: The Separation of Heaven and Earth

- Stuff, One in six Māori now living in Australia, research shows

- Te Papa Tongarewa – Museum of New Zealand, Tā moko | Māori tattoos: history, practice, and meanings

- New Zealand History, A history of New Zealand 1769-1914

- New Zealand History, Te Whiti biography

- New Zealand History, Whina Cooper biography

- NZ on Screen, Taika Waititi