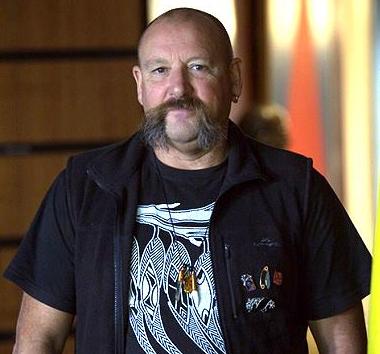

Mick Harding did not know he was Aboriginal for the first 25 years of his life. When he discovered his Aboriginality, he began trying to understand what it means through his art-making.

*This article is reproduced from Culture Victoria's interview with Uncle Mick Harding with permission from Sarah Rhodes, the copywrite owner.

My name's Mick Harding and I'm from the Yowung-Illam-Baluk and Yerrun-Illam-Baluk clans of the Taungurung people - a tribe of the Kulin nation. My clan country's sort of Mansfield area, so that's my connection.

Having the opportunity to be part of it (the possum skin cloak project) and then being asked to be the lead artist is a bit of a buzz for me. It’s a real opportunity to do something that our old people have done maybe 150-200 years ago. We're actually capturing that again and doing that again in a modern world.

The exciting part was that give and take of our symbols and of our stories from the past. To breathe some life back in them again. That was really, really exciting.

We are the first peoples of this land and have an ongoing responsibility to keep our culture alive and relevant into our current society. We belong to this land.

I’ve been part of cultural heritage for probably 20 years, I took all that sort of knowledge of things that I'd seen - Elders that I'd talked to, other Koori people that I'd talked to, and just loads and loads and loads of different types of observations

Mick Harding talks about the cultural significance of Boomerangs. He goes into what they are, what they're used for, the type of wood that is used to create them. Mick also discusses the Boomerang's spiritual significance.

So then I sort of thought that there's a few symbols that I could see that really were us and they were sort of half an arc shape - what would be called a chevron today or half a diamond. Since then I've just sort of taken those to be really dominant in lot of the stuff you see, throughout the whole of south-east Australia. Then I started to incorporate them in my own artwork prior to this.

So I suppose that was - you might even think of it as being my bias - and I took it into the process and wanted to incorporate that stuff. I think with all those things, what you see is you see whenever I've seen it from older shields or some cloaks that we've seen. There's one that we see that's got this sort of arc shape in it and it's used over and over and over and over again. And when you see the shields you'll have chevrons, but you won't have just one, you'll have chevron, chevron, chevron.

Once I found out about my heritage I kept getting involved in Indigenous affairs and stepping up to participate in more and more things for my community and here I am today.

So it all keeps going, keeps going, keeps going; it's just concentrations of it. I try to portray it like sort of a vibration of us, of the earth, of the animals, because I really don't know exactly, because one of my Elders has not passed that information onto me. So I just try and take all those observations and all those things that people have said to me and try to get them in the pot and mix them all together and try to make some sense of them. And that's the way I look because every time you see it, you see it's always not in just one form - it's always concentrations, like it's a vibration, and so I see that.

Image Source: Sarah Rhodes.

When you look at other art from other areas throughout Australia, you know when you look at those dot paintings, it's this constant continual stuff like a vibration, like a connection to that vibration, to that spiritual connection to that countryside. I sort of see it like that and try and then think about how I'm going to do it like that. I suppose that's what led us partly to do it like this as well because as I said before, I come with that sort of bias to it, so I'm trying to use that mindset on it and I'm still doing this art, you know. You look at any of my artwork that I'm doing today you'll see it constantly.

Our children’s future, Our culture, Your culture.

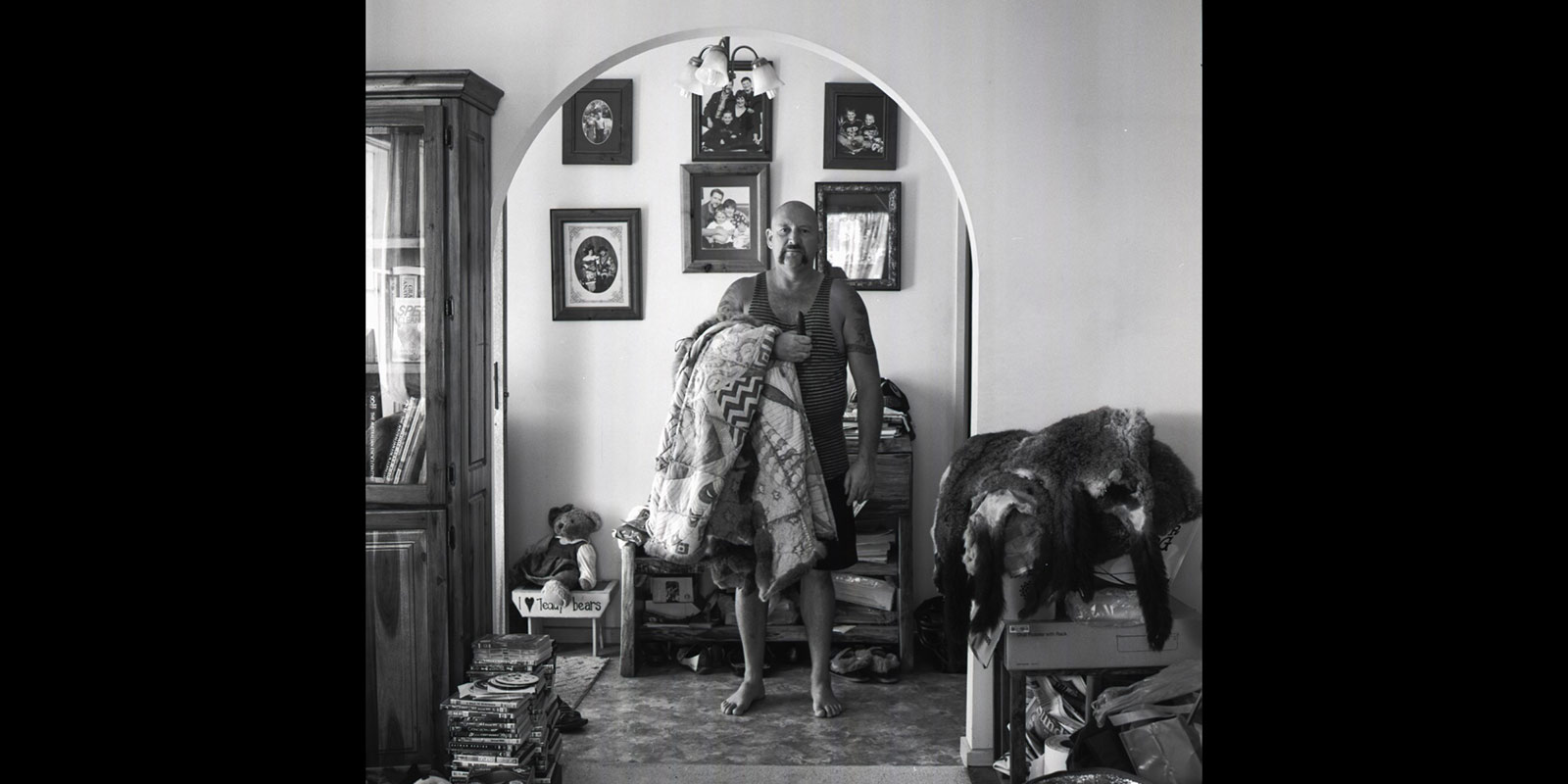

My children, Mitchil and Corey, they've taken part in every workshop that we did to craft the cloak which I thought was really important for me. And I suppose that the important part of that is that for the first 25 years of my life I never knew about my Aboriginality but they will know and have taken part in their culture from the outset, from when they're little kids.

So they'll have the first 25 years, and this is part of it. And they've done other things like language camps and cultural camps and dancing; they've been part of dance groups. I've really made sure they've been exposed to it and been part of it, and this is just another one of those sorts of things that I'm really conscious of and I really want them to know who they are and be proud of who they are.

Image Source: Sarah Rhodes.

Uncle Mick Harding made history by becoming the first Aboriginal person ever to address the Victorian Cabinet.

I feel privileged to have had that opportunity. I'm hoping that what I did and what I said makes them proud and other people proud.

To read more on this and Mick's involvement on this groundbreaking talks, follow the links below.

Victoria works towards treaty

Sources & Further Reading

- Interview: Taungurung Elder Mick Harding (Victorian Collections)

- Mick Harding - Ngarga Warendj

- Mick Harding demonstrates the ancient craft of wood burning for NAIDOC Week. (SBS)