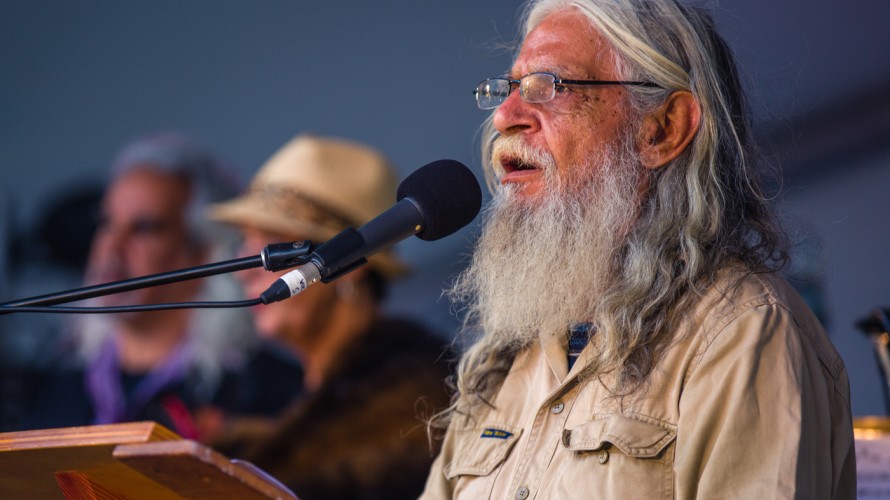

I'm of the Taunwurrung people but I was born up at Mooroopna. In 1956, I was rounded up from Daish's Paddocks, along with a lot of other people, and taken and put into an orphanage.

Article Source: Bunjilaka Melbourne Museum

I would have been not long past my second birthday. As I turned five they moved me into a boys’ home in Box Hill run by the Salvation Army. I knew I had a sister but that’s all we had, just us. She got fostered at five, but we somehow were able to keep in touch.

At the age of 10 or 11 the police pulled up and threw me in the divvy van and dragged me to the police station

From there I was fostered a few times till at eight I was fostered by an older couple. In the eyes of the police in them days, someone marked as a ward of the state meant that they were a troublemaker. At the age of 10 or 11 the police pulled up and threw me in the divvy van and dragged me to the police station, because I had a file, which I didn't know I had. From then on we had an ongoing misunderstanding. I reckoned they were beating me up for nothing so I started to do things.

I was 14 in Turana and the referendum had happened. I was in doing a little bit of time for just minor trouble and I joked with them, ‘hey, I'm a citizen now, does that mean you can let me out of here because I'm no longer a ward of the state?’ A few days later they passed me a letter that had been written in 1965. It was by a baby brother of mine, telling me about his mother's birthday. They all tried to have a party for her and instead she broke down and started crying. The letter said then, she told us about you and how you'd been taken. He informed me that he was my brother and there was another sister and another three brothers, and enclosed was a photograph of them and mum and their address.

So I went and visited. Under the state government rules at the time I had to go with my foster parents. My mother was a bit wary. Next time I went by myself and she was trying to tell me about the other brothers and sisters who'd been taken.

I got to be about 16, 17, and I had a pretty good probation officer. I was telling him I thought I had extra brothers and sisters and nobody seemed to know where they were. He asked me if I wanted a cup of tea while he opened my file. I said yes. I had an idea he was up to something. He left my file open and left the room. I had a look and there was my sister's address and the foster parents she was living with. I met her on the quiet and gradually we let her know that I was actually her brother. There was another brother but unfortunately it's taken till this year to find him. In the meantime, all the other aunties and uncles were telling me about their sons and daughters missing and some of them I knew from the orphanages. I didn't know back then that they were relatives.

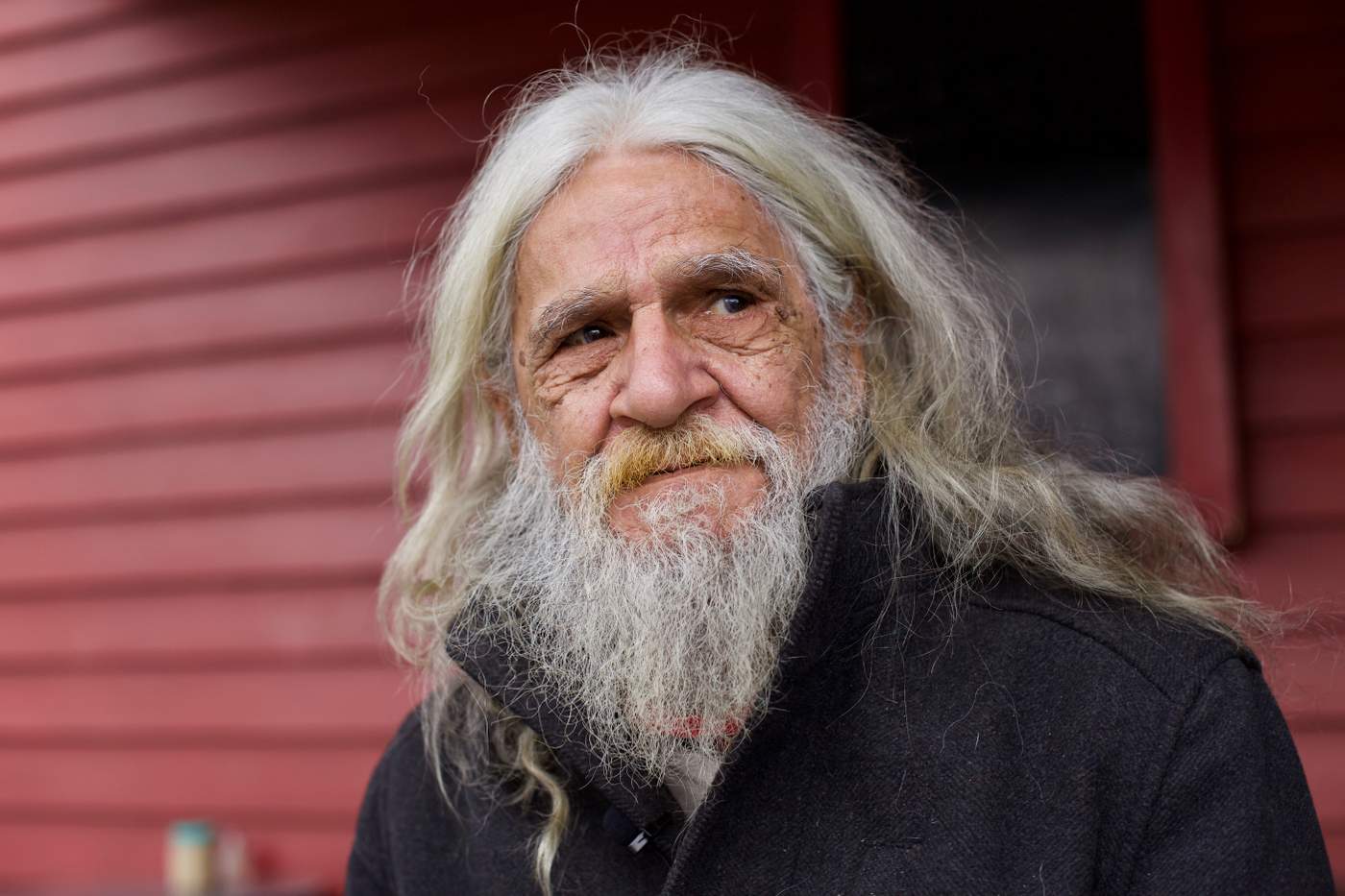

I realised then that I was supposed to have a leadership role in the family.

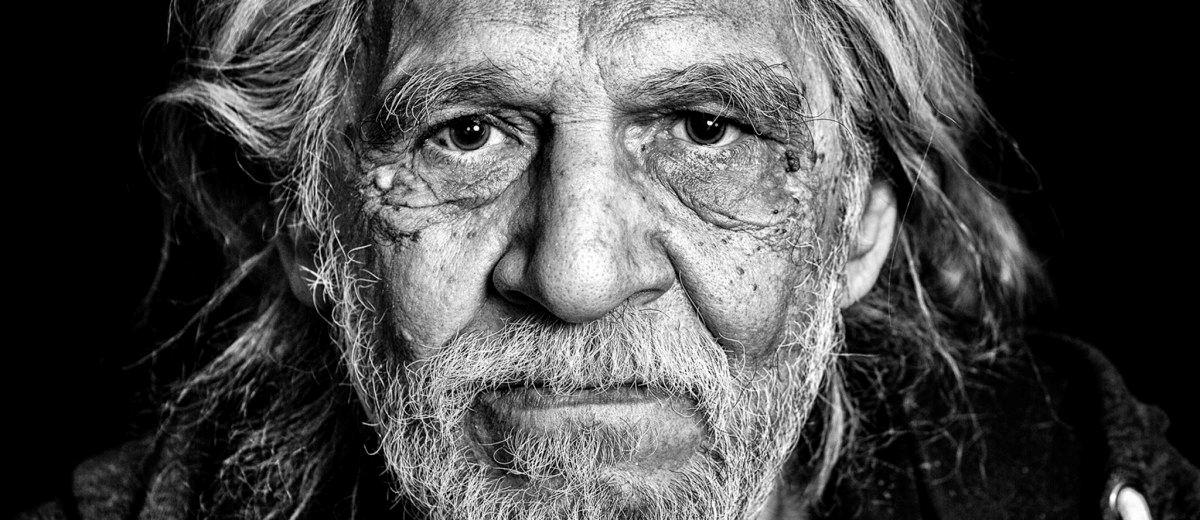

One day I went to the pub with a couple of older cousins and they got into trouble and their mum was telling them off. I'm thinking, I'm sweet, I'm safe, and then she started blasting me - as their Elder I should have known better. So I realised then that I was supposed to have a leadership role in the family.

I started fruit and vegie picking. A lot of Aboriginal people in them days were fruit and vegie picking. I was a young fella and they'd tell stories of the old days because they'd always go Walsh, eh? Who's Poppa Joe? Oh, that's my grandfather. He and Nanny Effie were looked at fondly and people would tell me stories about them.

Uncle Larry Walsh tells the tale of how the Kulin people were given fire by Bunjil, the creator, and follow the story of the first sparks in the Dandenong ranges.

My first outreach job with the Legal Service was going down to the Fitzroy Parkies. Half of them were from orphanages too. I started helping the boys. I'd go talk to the Aboriginal Housing Board, they’d tell me what restrictions they had or how I could bend the rules. Some of them had drug problems, alcohol, that was getting them into trouble. Over the years I've maintained friendships with them all. Every time I go down the park, the head Parkies always introduce me the new ones and say, this is Uncle Larry. They accepted me as the Uncle Grumpy and the Elder.

They were then starting to form groups like Aboriginal Community Elders. Because I'd been helping some of the homeless Aboriginals with their housing, they called me onto that... it's how I actually met Aunty Iris Lovett-Gardiner. Aunty Iris would yarn with me because she liked the way I did things. She talked to me about some of my rellies and how they as old people, because they weren't living with their family, no one was looking after them and they died alone. And she's gone, we're looking to get a place, an Aboriginal Elders' Hostel where they can stay. I helped organise for her to meet several ministers and on the way she'd yarn to me about the old days. I did OK at maths and more than OK at English, but I was always getting 90s for History at school. It was always one of my favourite subjects. So Aunty Iris is yarning to me about history and Uncle Stewart Murray is yarning to me and I'm listening and soaking it in. I helped them and so ACES (Aboriginal Community Elders Services) was built.

Next thing I know I'm on the state committee and national committee for Deaths in Custody.

In Moe / Morwell they were getting worried about the arrest rates. Some of the people who were getting arrested were dying because they were old, ill, and the police were picking them up because they were drunk. Even though I was no longer working for the Aboriginal Legal Service everybody would phone me. Next thing I know I'm on the state committee and national committee for Deaths in Custody. I'd started out just by myself helping get my family back together then other cousins back and it all seemed to lead to the same problem. All these people, some of them I knew, dying in jails and they're all coming from orphanage and foster home backgrounds.

When a few of us decided we had to do something about the Stolen Generations, we approached Lowitja O'Donoghue. She agreed to put it as an ATSIC issue, I think reluctantly, because she had a good foster home but she understood us who had it good have to look after the ones that didn't. We went public. We got the papers in and we've gone look we're sick of this. And we told a little bit of our story and we pushed. The minister took it to Paul Keating, Paul Keating agreed there needed to be an inquiry.

The minister took it to Paul Keating, Paul Keating agreed there needed to be an inquiry.

Every one of the investigators came and met me. By the time the inquiry was up, I'd been all around Victoria talking to everyone going. You've got to go. I went to every inquiry in Victoria. I felt my responsibility was to go and encourage. I'd see someone that'd just been in the inquiry start to look like they were about to crack up and I'd sit with them. I just keep my eye on everyone. I finally went in as a witness and the funny thing was that I never spoke about me. I spoke about two of my best mates who both took their own lives. I talked about their lives rather than my own because they were the ones who couldn't speak for themselves.

I don't think my work's finished and I don't think that it's just about the Sorry Day, the Stolen Generations, the deaths in custody, the fights I had with police over rights, it was also along the way people told me some beautiful things. Yulendj gives a chance for their stories to be told. Uncle Stewart would drag me to a few meetings and he'd just ask me to listen to a couple and tell him afterwards what I thought and then finally going, you talk to them. Aunty Iris taking me to meetings and saying I want my nephew here to speak! They were good people who did a lot of things themselves and they gave me a chance. I had a reputation, in and out of orphanages and youth training centres and prison, a very tough character. And here's all these old men and women, they're the ones who built everything, going oh yeah, but we see him, he's a nice person really. For me, Yulendj (the Melbourne Museum Bunjilaka Community Reference Group) is about letting people know about good people who helped get things going. We all know them by name or reputation but the stories aren't there.

And that's what Yulendj is about, getting stories out about people like that.